Exclusive look at Cruise’s first driverless car without a steering wheel or pedals

…

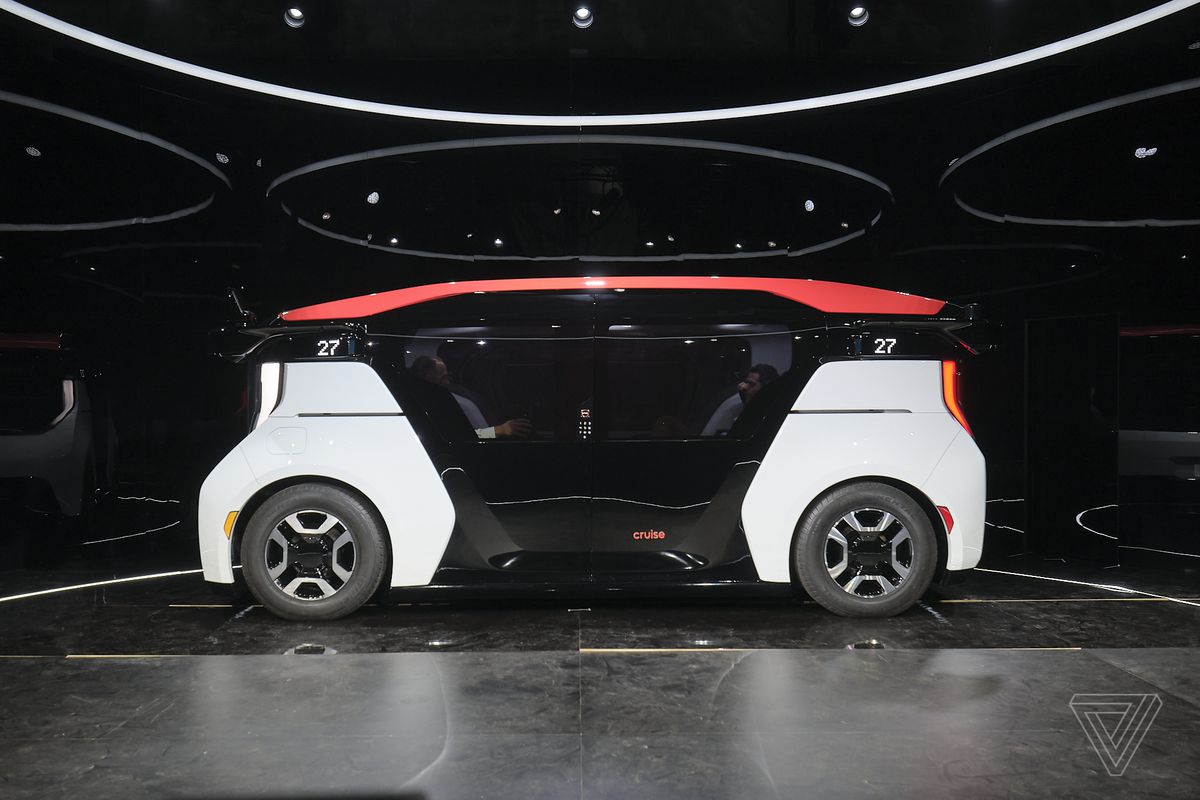

The not-a-car sits on the gleaming black stage surrounded by a halo of light. It’s orange and black and white, and roughly the same size as a crossover SUV, but somehow looks much larger from the outside. There is no obvious front to the vehicle, no hood, no driver or passenger side windows, no side-view mirrors. The symmetry of the exterior is oddly comforting.

I am one of the first non-employees to see it, after being invited by self-driving company Cruise to come out to San Francisco for an early look. And what I see is a car. A weird-looking car, sure, but a car nonetheless. That’s what my brain tells me. But the company insists I’m not seeing what I’m seeing. One employee refers to it as “the property.”

It’s easier to describe what it’s not, rather than what it is. For example, it doesn’t look like a toaster on wheels, as some autonomous “people movers” tend to do. A microwave might be more accurate, but I’m not convinced.

Its official name is “Origin,” and Kyle Vogt, the co-founder and chief technology officer of Cruise, is clearly excited to be showing it off. With a broad smile, he reaches out and touches a button on the side, causing the doors to slide open with a little whoosh like something out of Star Wars.

Inside are two bench seats facing each other, a pair of screens on either end… and nothing else. The absence of all the stuff you expect to see when climbing into a vehicle is jarring. No steering wheel, no pedals, no gear shift, no cockpit to speak of, no obvious way for a human to take control should anything go wrong. There’s a new car smell, but it’s not unpleasant. It’s almost like cucumber-infused water.

“The way vehicles are designed, normally they have a hood in the front where the engine is and some storage in the trunk,” Vogt says, as we sit across from each other. “But when you don’t need all that stuff… we can have this enormous, spacious cabin without taking up any more space on the road than a regular car would. Which is kind of insane.”

But the Origin is arriving into an unforgiving world: half of Americans are skeptical to the point of being fearful about self-driving cars. They don’t mind a car that can drive itself — as long as they can take over when they choose. That’s impossible with this vehicle. I ask Vogt where he gets the confidence to take away everything we’ve come to associate with human driving.

“I guess it’s important to note that we haven’t validated and released our technology yet,” he says. “So we haven’t gone out there and said it’s safer than a human and getting ready for prime time. But we’re getting pretty close.”

Approximately 18 minutes later, after a brief tour of the vehicle and back-and-forth about the company’s grand plans for the Origin, Vogt says something bolder. “By the time this vehicle goes into production, we think the core software that drives our AVs will be at a superhuman level of performance and safer than the average human driver,” he says. “And we’ll be providing hard empirical evidence to back up that claim before we put people in a car without someone in it.”

Cruise has often been described as a “division” or “unit” of General Motors, but the company prefers “majority owned subsidiary.” (The automaker technically owns two-thirds of Cruise, which it bought in 2016.) However, GM isn’t the only major automaker in Cruise’s corner. In October 2018, Honda announced its plan to invest $2.75 billion in Cruise over 12 years. The company has also raised money from Japan’s SoftBank Vision Fund and T. Rowe Price, and has a valuation of $19 billion.

As part of the Honda deal, GM teamed up with the Japanese automaker to design a “purpose-built” self-driving car. A “purpose-built car” is not a normal car retrofitted to be self-driving, as a majority of the autonomous vehicles on the road today are. Rather, it’s a car designed from the ground up to drive itself. That would be in addition to the steering wheel-and-pedal-less Chevy Bolt that GM and Cruise are working on. At the time, Vogt teased a vehicle with “giant TV screens, a mini bar, and lay-flat seats.”

The Origin has none of these amenities, but Vogt insists its real asset is its modularity. “We built this car around the idea of not having a driver and specifically being used in a ride-share fleet,” he says. “This vehicle is engineered to last a million miles and all the interior components are replaceable. The compute is replaceable, the sensors are replaceable. And what that does is it drives the cost per mile down way lower than you could ever reach if you took a regular car and tried to retrofit it. The replacement cost and the upkeep of that would just kill you from a business standpoint.”

I don’t typically hear AV companies talk about “unit economics” and profitability. But that’s going to creep up sooner than a lot of people realize, Vogt says. Experts estimate that each self-driving car could cost upward of $300,000-$400,000, when taking into account the expensive sensors and computing software needed to allow the vehicles to drive themselves. Recouping those costs will be enormously challenging, and Cruise is trying to address that by building a car with more staying power than most personally owned vehicles.

Cruise has been working on the design of the Origin for over three years, but Honda’s involvement “super charged” the effort. The two automakers didn’t collaborate on every tiny detail; instead, they split up the work based on their expertise. GM was responsible for the base vehicle design and the electric powertrain, while Honda helped create the interior’s “efficient use of space,” Vogt says. Meanwhile, Cruise handled the sensing and computing technologies, as well as the experience from the rider’s standpoint.

Vogt allows that the sensor suite could change before the vehicle goes into production. But right now, it has the standard configuration found in many AVs on the road today: radar, cameras and LIDAR laser sensors. The hard drive, stored in the trunk and housing the vehicle’s artificial intelligence and perception software, is cooled by the vehicle’s battery system, making it quieter and less prone to overheating than previous iterations. That means passengers riding in the forward-facing seats won’t have to experience overly toasty tushies (as I have riding with another AV operator).

Cruise, with Honda’s help, designed the interior of the vehicle primarily for shared rides. The screens, one on either side, will display an itinerary for picking up and dropping off each passenger, so riders know what to expect. Carpooling in the age of smartphones hasn’t exactly been the runaway success that ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft have hoped. But Cruise thinks its abundance of space can help minimize the friction.

“It’s designed to be comfortable if it’s shared, but if it’s just you, you’ve got so much space in here you can really like stretch out,” he says, extending his legs so his feet almost touch mine. Almost, but not quite.

Look, as far as I’m concerned, Cruise’s Origin is a car. Cruise says it wants to “move beyond the car,” but I’m not convinced the absence of certain controls negates its inherent car-ness. As Vogt points out, it occupies the same amount of space as an SUV, and Cruise claims it can travel at normal city speeds. It is a car-like shape and does car-type things, like traveling down a road with people in it. And if there isn’t another good name for it — “the property” notwithstanding — then “car” will have to do.

I don’t begrudge the company for attempting to argue otherwise. The push for not-car-ness is evident in Cruise’s intense marketing campaign leading up to the unveiling of the Origin. The company recently emptied out its Instagram account — so long, photos of smiling people riding in the company’s fleet of self-driving Chevy Bolts — and posted a series of cryptic longitude and latitude coordinates that correspond with famous historical moments, like the invention of the compass and the steam locomotive. Not-car inventions that seriously changed how we travel, in other words.

Even so, Cruise isn’t the first company to build and test a self-driving car without traditional controls. In December 2016, Google stunned the world when it revealed that it had put a blind man in one of its egg-shaped autonomous test vehicles and sent him out for a short ride around Austin, Texas. Google’s Firefly vehicle, audaciously designed by YooJung Ahn, is widely considered to be the first car tested publicly without a steering wheel or pedals.

Waymo, the company spun out of Google’s self-driving project, retired the Firefly in 2017. But in a recent podcast interview, Waymo CEO John Krafcik voiced curiosity that no one has replicated the feat since. “Why do you think no one has done that yet?” Krafcik said on the Autonocast. “Because we all sort of scratch our heads and say, ‘Is there not the capability there? Or folks have the capability but they’ve chosen not to do it or not to show it?’”

Cruise hasn’t been as forthcoming with its technology as Waymo. The company has only hosted one demo ride for journalists in 2017, which produced embarrassing headlines such as Reuters’ “Taco truck halts GM autonomous car’s cruise through city streets.”

There have been other bumps in the road as well. Cruise’s plan to test its vehicles in New York City — arguably the most difficult driving environment in the US — went nowhere. In July 2019, the company announced that it would miss its goal of launching a large-scale self-driving taxi service by the end of the year. It tried to sugarcoat the disappointing news by announcing a plan to dramatically increase the number of its test vehicles on the road in San Francisco.

Coming right on the heels of the Consumer Electronics Show and its cavalcade of concept cars and design projects, there’s a sense that Cruise is trying to beat back diminishing expectations. The past year has been a pretty bad one for believers in the technology: missed deadlines, rising concerns over safety, and the growing belief that making autonomous vehicles will be harder, slower, and more expensive than previously thought.

Cruise is trying to recapture some of that early magic with this vehicle. But it’s also attempting to be more pragmatic and attuned to the realities of growing and scaling a real business.

Of course, bureaucracy and politics could drive the whole thing right off the road.

Remember the unsettling lack of steering wheel, break pedals, and so on? That means the Cruise’s not-car will require an exemption from the federal government’s motor vehicle safety standards. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration only grants 2,500 petitions a year. GM submitted a petition for permission to deploy a fully driverless Chevy Bolt in 2018, but it has yet to receive a response. And it will most likely need another exemption before the Origin is allowed to hit the road, too.

Safety advocates are urging NHTSA to take its time in deliberating these changes. For example, the Center for Auto Safety “strongly question[s]” the NHTSA’s decision to prioritize these rule changes considering self-driving cars are still in their “infancy and quite likely decades away from widespread practical utility.” And the National Automobile Dealers Association, meanwhile, takes issue with the use of the term “barriers” to describe current safety standards and argues that self-driving cars should continue “to allow also for human control.”

GM isn’t the only company seeking to fast-track these changes. Ford has said it will build an autonomous car without a steering wheel or pedals by 2021, while Waymo has begun offering a limited number of rides in fully driverless minivans to its customers in Phoenix, Arizona.

Cruise is clearly feeling the heat from its competitors, especially when you consider that it has yet to take the important step of launching a commercial business. The company has a beta ride-hailing service, but it’s only available to employees, and Cruise won’t say when it will be available to the broader public. The company also won’t say when the Origin will roll out, but promises to share more information about its production plans in the future. (It’s already been burned once when it missed its 2019 robo-taxi deadline, so it seems the company wants to be careful that doesn’t happen again.)

I have so many more questions — about the sensor suite, the business model, the testing (if any) that Cruise has conducted — but I’m informed that our time is done. The event is being managed by a unionized workforce, and any additional time could cost Cruise an additional $12,000. I thank Vogt for his time and jokingly ask if there’s an “abort” button in the vehicle.

“I think it’s been pushed,” he says, grinning. “You just go straight through the ceiling.”