The cost of at-home covid-19 tests signals the failed US approach to public health

Rapid antigen tests are harder to find and more expensive in the US than elsewhere in the world, because of how America does public health …

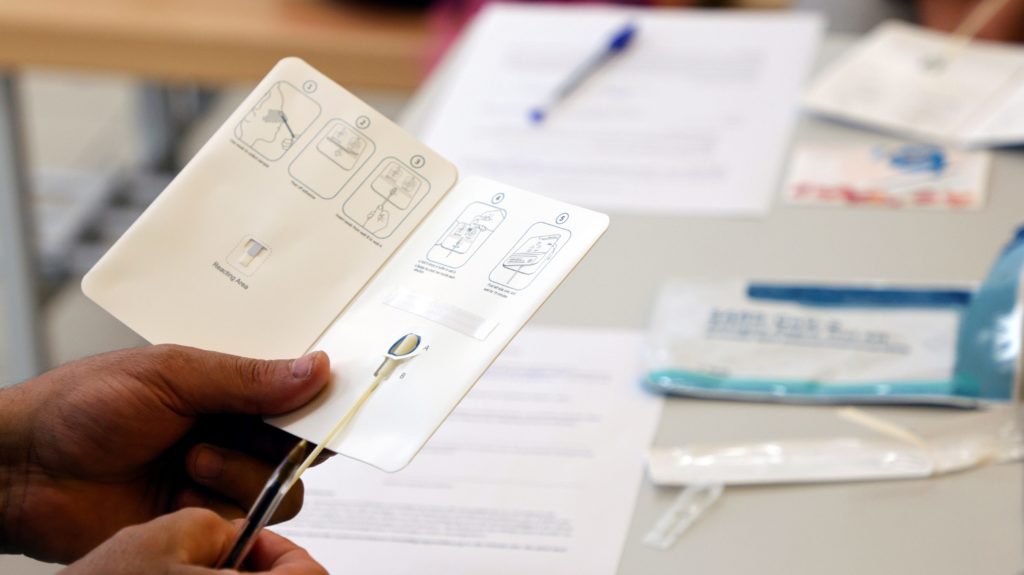

At-home rapid covid-19 tests are a key to everyday life in many parts of the world. They only take 15 minutes and can tell, with a reasonable degree of accuracy, if someone has been exposed to covid-19.

Want to have a few people over for dinner? Ask your guests to swab before they arrive. Feel a scratchy throat? Swab. Visiting an older or at-risk person and want peace of mind? Swab.

At-home antigen tests quickly detect certain proteins in the virus that trigger the production of antibodies, while polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, which are more accurate but more complicated and slower, look for the genetic material of the virus.

Rapid at-home tests aren’t foolproof and false negatives are common in cases of asymptomatic or early-stage infections. But they present an important tool to control the spread of the disease while trying to resume regular activities.

This isn’t hard to do when tests are cheap and easily available. In Germany, at-home tests sell for €0.7 (or about $1) each. In other European countries, they range from less than €1 to a couple of euros. In the UK, they are free, and can be ordered online from a government site or collected in libraries, pharmacies, and other locations. In Canada, the government provides businesses with free testing for workplace screening.

But in the US, tests range from $9 each to $24 for a box of two (which are more commonly available). They are only sold in pharmacies, and hardly an everyday tool at the level of a mask, or hand sanitizer.

The reason rapid tests are so scarce in the US has to do with regulations imposed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the market. But it’s also a product of a fundamentally different approach to public health.

US public health favors clinical considerations over social ones

Public health is a political and social science as much as—if not more than—it is a clinical one. Its concerns expand beyond the strict realm of medicine and to handling the social determinants of health—such as socioeconomic status, discrimination, and violence. Yet while in some countries—chiefly, European ones—the public health field is led primarily by social considerations, in the US it is led by clinical ones.

This is rooted in the history of America’s medicine. Since healthcare in the US was professionalized with the Flexner Report in 1910, a report establishing the guidelines for practicing medicine in the US, the field has favored a biomedical approach to medicine. That approach, which focuses nearly exclusively on clinical measures, is in contrast to a so-called biopsychosocial one, which addresses individual health as a function of the broader social context. The consequences of this approach can be seen in all aspects of America’s health, from the tendency to overmedicalize childbirth to the creation of a system where access to highly specialized treatments is prioritized over making healthcare available for all.

With covid-19, this approach has meant clinical interventions—such as vaccines and treatments—have been emphasized over more society-based measures. The scarcity of rapid, at-home antigen testing exemplifies this.

Antigen tests in the US are expensive, and not so easily accessible because there are only very few manufacturers that have received the FDA’s emergency authorization to make them. The process to obtain that authorization is burdensome and complex, and designed to hold the tests to accuracy standards hard to achieve for many manufacturers. Startups trying to produce low-cost rapid tests have been delayed in obtaining authorizations, while the few manufacturers (12 in total so far) that have been able to get their test cleared have the freedom to set the price as high as the market will bear.

By comparison, the European Union, which doesn’t hold rapid tests to the same standards as lab ones, has approved more than 100 rapid tests (pdf). Not only are the prices lower because the competition is higher, but because many governments subsidize the prices of the tests, or purchase and distribute them directly, with the goal of making it as ubiquitous as possible.

The absolute accuracy of a test is paramount only from a clinical perspective, and public health experts have called out these standards as unreasonable. Instead, having more tests available, even if they are a little less accurate, would control the spread of the virus, and help people make more informed decisions as they go about their lives with the pandemic still ongoing.

Further, the PCR tests, which are the ones the US is primarily relying upon, are not necessarily the best option when it comes to understanding and controlling the epidemic.

“A pandemic is first a public health crisis and secondarily a medical crisis, but our management of the pandemic has been dictated by medical clinical logic,” says Eric Reinhart, a physician and anthropologist at Northwestern University. “The PCR test, which is much more sensitive, will show you a trace amount of the virus before somebody is even infectious and after they’re no longer infectious. From a clinical perspective, that seems like a superior test, but from a public health perspective, it’s a nightmare, because you’re detecting positive cases in people who are no longer infectious.”

The risk of not having at-home tests

With the omicron variant set to spread widely in the US, and cases of covid-19 surging across the country, access to at-home rapid testing is essential. At-home testing would help get better data on where the outbreaks are occurring, and the arrival of new antiviral drugs that work best in the early stages of infection would provide an important indicator of whether someone needs to be treated.

People could have covid-19-like symptoms from the seasonal flu, and having a test could spare healthcare resources if they can test their status at home, rather than going to health facilities to seek treatment.

Instead, test supplies tend to be scarce in areas with surges, and even when they are available they’re too expensive to become a routine purchase. “The populations that we probably should be testing most often using these tests, for example intergenerational families, people who are working essential frontline jobs, those seem to be the people who would be most priced out of the tests,” says Nora Kenworthy, a professor of public health at the University of Washington Bothell.

Those who can’t access at-home rapid tests are unlikely to take routine PCR tests because they might be worried about costs, or don’t have the time or inclination to get to a testing location. Further, even those who take the PCR tests often continue to go about their lives until they wait for the results, which can take up to three days, potentially exposing others to covid-19, says Kenworthy.

Although the US has lagged in rapid test availability so far, it doesn’t mean it has to continue doing so. Although increasing test supply might take time, at least the government could impose limits on the pricing of the tests, subsidize them, or purchase them to distribute for free. Some states are doing so already: Ohio distributed free rapid tests in libraries and other locations, and so did Colorado.