The surprising history of business school classes for executive wives

Business schools once helped socialize their students’ wives to be the ideal partners of aspiring executives. …

Picture a US business school in the 1950s.

You might imagine imposing brick buildings with men, mostly white, mostly affluent, flowing through the hallways. You might also imagine that, with the rare exception, the only women in the b-school hallways are assistants and secretaries—not students. But there you’d be wrong.

Women did attend business schools well before these institutions became official co-ed spaces, just not in the way you might expect.

Four years ago, Allison Louise Elias, a gender historian and assistant professor at University of Virginia Darden School of Business learned that women were welcomed into business schools as the wives of businessmen enrolled in then-new executive business programs—short, intensive courses for men aspiring to leadership positions. Think of it like a “finishing school” for executive wives, says Elias.

At Harvard, for example, in the last week of the executive education program, the students’ partners (i.e., wives) would be invited to make a trip to Cambridge to join their husbands who had been away from home for 12 weeks, living in dormitories. The wives could “see what their husbands had been up to,” says Elias, and could become acquainted with business culture. Other programs invited wives to campus for a weekend or a day, here or there.

While their husbands might be learning how to navigate the upper echelons of management, the wives might study the Cha-Cha-Cha or visit a local museum to take in some high culture. It was thought that this coaching would prep the wives to support their husbands as they climbed the corporate ranks, says Elias, who co-authored a new paper about executive wives with Rolv Petter Amdam, a Norwegian business historian.

“The programs approached women as a group of outsiders who should be socialized into the norms and values necessary to support their coming executive husbands, and should share this new role,” the pair write. That meant “cultivating a separate and distinct skill set that men didn’t have—a lot of entertaining skills, more domestic skills, being a consummate hostess, dancing,” says Elias.

The forgotten history of executive wives’ “education” is another clue in explaining why, even today, business schools, and proverbial corner offices remain male-dominated spaces, Elias says. Back then, business schools were deeply committed to the “separate spheres” ideology, which dictated that men belonged in the workplace and women at home—or perhaps, for women of a certain social status, at a charity luncheon writing checks. The idea has stuck around, if in less conspicuous ways, in part due to imprint theory, a concept in organizational studies, which suggests that the norms established during an institution’s formative years—in this case the early years of business schools—are particularly durable, Elias explains. That’s why today’s MBA programs can’t afford to ignore this piece of history.

Piecing together the historical record

Executive wives’ education was not uncommon in business schools across the US, but finding credible evidence about their curricula was challenging “because of the way our historical record reflects what we think is important,” says Elias. “There was not necessarily a box of documents on corporate wives.”

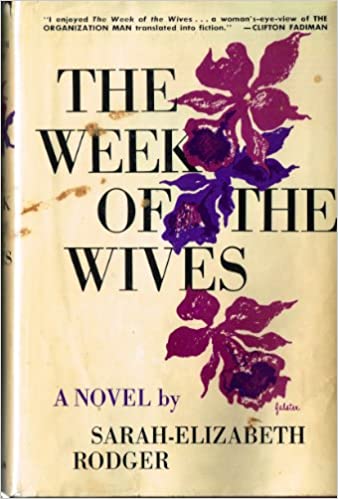

After scouring the archives at four schools—Harvard Business School, MIT Sloan School of Management, the Wharton School and Stanford’s Graduate School of Business—Elias and Amdam began pulling details from academic literature and business magazine articles. They even discovered a 1958 novel that explored the emotional landscape of a wives’ week at Harvard Business School and the tensions it raised within one fictitious couple whose wife offered her husband too many opinions about corporate strategy. Other details from the plot spoke volumes, too: That one man doesn’t have a wife to bring to wives’ week “is looked on with a bit of sadness,” says Elias. “He has to figure out what he’s going to say about that.”

Wives’ weeks at business schools were a response to corporate “wife screenings”

Executive business programs were first offered on college campuses in the post-war period, starting at Harvard Business School in 1945. Around that time, companies began to conduct “wife screenings” when choosing who to hire and promote, a practice that persisted until the 1970s, despite 60s-era civil rights laws that prohibited employers from considering familial status in the hiring process.

Wives could make or break their husband’s career, Elias explains. When a man (and yes, it was almost always a man) was up for a promotion, his boss would be sure to vet his spouse, too, whether at an interview in the corporate office or informally at a dinner party.

Would the wife accept that the company came first? Would the wife follow her husband to multiple postings? Could she be charming at galas? Would she sparkle as a hostess or would she have one cocktail too many? Would her behavior and pedigree reflect well on the business? Were there areas of concern: too feisty, too political, too shy?

In a strange sense, these customs—the “finishing school” classes and the screenings—also acknowledged the sheer amount of unpaid labor that went into being a businessman’s wife. The companies understood the effect a wife could have on a business’s bottom line. They did not try to pretend that the globe-trotting executive could also manage family life and raise children while resettling periodically in a new city.

Essentially what you had was akin to a business partnership. “The wife was very integral to her husband’s career success,” says Elias. “Even though she had a distinctive role, she was definitely bolstering him.”

Today, many partners are still expected to fulfill similar social and familiar duties, irrespective of whether or not they have their own career. Among the corporate elite, it “certainly doesn’t hurt,” says Elisa, to project the image of an “engaged and supportive partner or family behind you.”

How the spirit of the wives clubs persists

Of course, b-schools circa 2022 are hardly a mirror image of business schools in the 1950s.

More women than ever are attending business schools, according to the Forté Foundation, a nonprofit that supports women entering MBA programs and advocates for gender equity at 54 top business schools around the world. In 2021, Forté found that 41% of MBA students at its 54 member schools were women, up from 39% in 2020. Three of the foundation’s 54 global member schools—George Washington School of Business, Wharton, and Johns Hopkins University’s Carey School of Business—have reached gender parity.

Still, Elias feels the spirit of “wives clubs” persists in business schools today, though of course the clubs aren’t limited to wives. The “Wharton Wives Club” is now the “Partners Club” to account for different types of partnerships, for example. Stanford has a robust community of significant others or “SOs” and Harvard has a Partners and Families club.

And while business schools should celebrate that their student bodies better reflect the general population, Elias says, they have been slow to think about how they might attract students who have obligations outside of coursework and social events. That’s because business schools are still crafting prototypical “ideal workers” for the workplaces that—work-life balance pledges notwithstanding—seek to hire them.