WellSaid aims to make natural-sounding synthetic speech a credible alternative to real humans

Many things are better said than read, but the best voice tech out there seems to be reserved for virtual assistants, not screen readers or automatically generated audiobooks. WellSaid wants to enable any creator to use quality synthetic speech instead of a human voice — perhaps even a synthetic version of themselves. …

Many things are better said than read, but the best voice tech out there seems to be reserved for virtual assistants, not screen readers or automatically generated audiobooks. WellSaid wants to enable any creator to use quality synthetic speech instead of a human voice — perhaps even a synthetic version of themselves.

There’s been a series of major advances in voice synthesis over the last couple years as neural network technology improves on the old highly manual approach. But Google, Apple, and Amazon seem unwilling to make their great voice tech available for anything but chirps from your phone or home hub.

As soon as I heard about WaveNet, and later Tacotron, I tried to contact the team at Google to ask when they’d get to work producing natural-sounding audiobooks for everything on Google Books, or as a part of AMP, or make it an accessibility service, and so on. Never heard back. I considered this a lost opportunity, since there are many out there who need such a service.

So I was pleased to hear that WellSaid is taking on this market, after a fashion anyway. The company is the first to launch from the Allen Institute for AI (AI2) incubator program announced back in 2017. They do take their time!

Talk the talk

I talked with the co-founders CEO Matt Hocking and CTO Michael Petrochuk, who explained why they went about creating a whole new system for voice synthesis. The basic problem, they said, is that existing systems not only rely on a lot of human annotation to sound right, but they “sound right” the exact same way every time. You can’t just feed it a few hours of audio and hope it figures out how to inflect questions or pause between list items — much of this stuff has to be spelled out for them. The end result, however, is highly efficient.

“Their goal is to make a small model for cheap [i.e. computationally] that pronounces things the same way every time. It’s this one perfect voice,” said Petrochuk. “We took research like Tacotron and pushed it even further — but we’re not trying to control speech and enforce this arbitrary structure on it.”

“Their goal is to make a small model for cheap [i.e. computationally] that pronounces things the same way every time. It’s this one perfect voice,” said Petrochuk. “We took research like Tacotron and pushed it even further — but we’re not trying to control speech and enforce this arbitrary structure on it.”

“When you think about the human voice, what makes natural, kind of, is the inconsistencies,” said Hocking.

And where better to find inconsistencies than in humans? The team worked with a handful of voice actors to record dozens of hours of audio to feed to the system. There’s no need to annotate the text with “speech markup language” to designate parts of sentences and so on, Petrochuk said: “We discovered how to train off of raw audiobook data, without having to do anything on top of that.”

So WellSaid’s model will often pronounce the same word differently, not because a carefully manicured manual model of language suggested it do so, but because the person whose vocal fingerprint it is imitating did so.

And how does that work, exactly? That question seems to dip into WellSaid’s secret sauce. Their model, like any deep learning system, is taking innumerable inputs into account and producing an output, but it is larger and more far-reaching than other voice synthesis systems. Things like cadence and pronunciation aren’t specified by its overseers but extracted from the audio and modeled in real time. Sounds a bit like magic, but that’s often the case when it comes to bleeding-edge AI research.

And how does that work, exactly? That question seems to dip into WellSaid’s secret sauce. Their model, like any deep learning system, is taking innumerable inputs into account and producing an output, but it is larger and more far-reaching than other voice synthesis systems. Things like cadence and pronunciation aren’t specified by its overseers but extracted from the audio and modeled in real time. Sounds a bit like magic, but that’s often the case when it comes to bleeding-edge AI research.

It runs on a CPU in real time, not on a GPU cluster somewhere, so it can be done offline as well. This is a feat in itself, since many voice synthesis algorithms are quite resource-heavy.

What matters is that the voice produced can speak any text in a very natural sounding way. Here’s the first bit of an article — alas, not one of mine, which would have employed more mellifluous circumlocutions — read by Google’s WaveNet, then by two of WellSaid’s voices.

The latter two are definitely more natural sounding than the first. On some phrases the voices may be nearly indistinguishable from their originals, but in most cases I feel sure I could pick out the synthetic voice in a few words.

That it’s even close, however, is an accomplishment. And I can certainly say that if I was going to have an article read to my by one of these voices, it would be WellSaid’s. Naturally it can also be tweaked and iterated, or effects applied to further manipulate the sound, as with any voice performance. You did’t think those interviews you hear on NPR are unedited, did you?

The goal at first is to find the creatives whose work would be improved or eased by adding this tool to their toolbox.

“There are a lot of people who have this need,” explained Hocking. “A video producer who doesn’t have the budget to hire a voice actor; someone with a large volume of content that has to be iterated on rapidly; if English is a second language, this opens up a lot of doors; and some people just don’t have a voice for radio.”

It would be nice to be able to add voice with a click rather than just have block text and royalty-free music over a social ad (think the admen):

I asked about the reception among voice actors, who of course are essentially being asked to train their own replacements. They said that the actors were actually positive about it, thinking of it as something like stock photography for voice; get a premade product for cheap, and if you like it, pay the creator for the real thing. Although they didn’t want to prematurely lock themselves into future business models, they did acknowledge that revenue share with voice actors was a possibility. Payment for virtual representations is something of a new and evolving field.

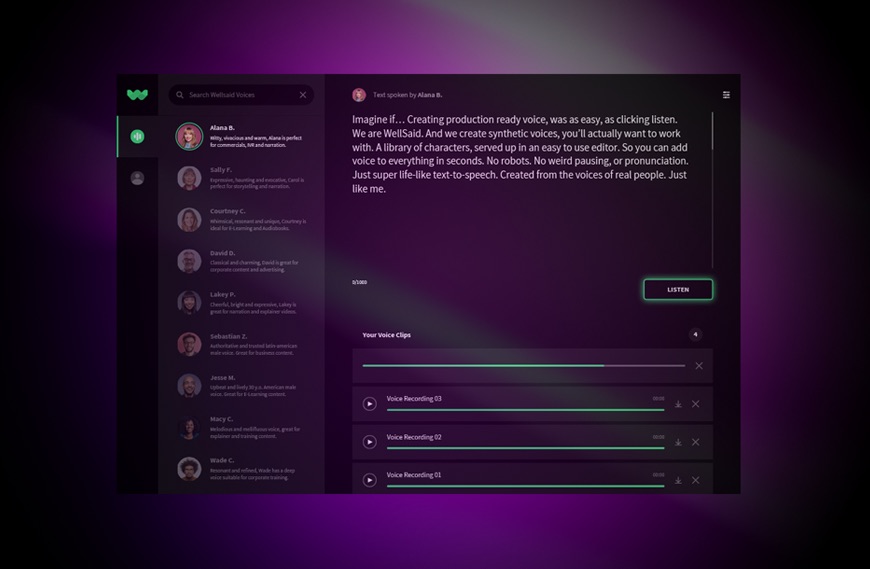

A closed beta launches today, which you can sign up for at the company’s site. They’re going to be launching with five voices to start, with more voices and options to come as WellSaid’s place in the market becomes clear. Part of that process will almost certainly be inclusion in tools used by the blind or otherwise disabled, as I have been hoping for years.

Sounds familiar

And what comes after that? Making synthetic versions of users’ voices, of course. No brainer! But the two founders cautioned that’s a ways off for several reasons, even though it’s very much a possibility.

“Right now we’re using about 20 hours of data per person, but we see a future where we can get it down to 1 or 2 hours while maintaining a premium lifelike quality to the voice,” said Petrochuk.

“And we can build off existing datasets, like where someone has a back catalog of content,” added Hocking.

The trouble is that the content may not be exactly right for training the deep learning model, which advanced as it is can no doubt be finicky. There are dials and knobs to tweak, of course, but they said that fine-tuning a voice is more a matter of adding corrective speech, perhaps having the voice actor reading a specific script that props up the sounds or cadences that need a boost.

They compared it with directing such an actor rather than adjusting code. You don’t, after all, tell an actor to increase the pauses after commas by 8 percent or 15 milliseconds, whichever is longer. It’s more efficient to demonstrate for them: “say it like this.”

Even so getting the quality just right with limited and imperfect training data is a challenge that will take some serious work if and when the team decides to take it on.

But as some of you may have noticed, there are also some parallels to the unsavory world of “deepfakes.” Download a dozen podcasts or speeches and you’ve got enough material to make a passable replica of someone’s voice, perhaps a public figure. This of course has a worrying synergy with the existing ability to fake video and other imagery.

This is not news to Hocking and Petrochuk. If you work in AI this kind of thing is sort of inevitable.

“This is a super important question and we’ve considered it a lot,” said Petrochuk. “We come from AI2, where the motto is ‘AI for the common good.’ That’s something we really subscribe to, and that differentiates us from our competitors who made Barack Obama voices before they even had an MVP [minimum viable product]. We’re going to watch closely to make sure this isn’t being used negatively, and we’re not launching with the ability to make a custom voice, because that would let anyone create a voice from anyone.”

Active monitoring is just about all anyone with a potentially troubling AI technology can be expected to do — though they are looking at mitigation techniques that could help identify synthetic voices.

With the ongoing emphasis on multimedia presentation of content and advertising rather than written, WellSaid seems poised to make an early play in a growing market. As the product evolves and improves, it’s easy to picture it moving into new, more constrained spaces, like time-shifting apps (instant podcast with 5 voices to choose from!) and even taking over territory currently claimed by voice assistants. Sounds good to me.