Despite global headwinds, Chinese hardware startups remain to take on the world

Bill Zhang lowered himself into lunges on a squishy mat as he explained to me the benefits of the full-body training suit he was wearing. We were in his small, modest office in Xili, a university area in Shenzhen that’s also home to many hardware makers. The connected muscle stimulator attached to the suit, called […]

Bill Zhang lowered himself into lunges on a squishy mat as he explained to me the benefits of the full-body training suit he was wearing. We were in his small, modest office in Xili, a university area in Shenzhen that’s also home to many hardware makers. The connected muscle stimulator attached to the suit, called Balanx, is designed to bring so-called electronic muscle stimulation, which is said to help improve metabolism and burn fat.

“We are not really aiming at Chinese consumers at this point,” said Zhang, who started Balanx in 2014. “The suit is for the more savvy consumers in the West.”

Prospects for hardware makers were looking bright until two years ago when the Trump administration began setting trade barriers on China. Relations between the two countries have been deteriorating over a series of flashpoint events, from Beijing’s policy on Hong Kong to the coronavirus pandemic.

Chinese entrepreneurs don’t expect relationships between the countries to warm up anytime soon, but many do believe the new office will make “less erratic” and “more rational” policy decisions, according to conversations TechCrunch had with seven Chinese hardware startups. Chinese tech businesses, big or small, are adapting swiftly in the new era of U.S.-China competition as they continue to woo overseas customers.

Designed in China

Zhang is just one of the many entrepreneurs looking to bring state-of-the-art Chinese hardware to the world. This generation of founders no longer hawk cheap electronic copycats, the image attached to the old “Made in China” regime. Decades of knowledge transfer, product development, manufacturing, export practice and policy support have made China a powerhouse for producing new technologies that are both edgy and still widely affordable.

The Balanx smart training suit / Source: Balanx

Anker’s power banks, Roborock’s vacuums and Huami’s fitness trackers are just a few items that have gained loyal followings in several overseas markets, not to mention global household names like Huawei, Xiaomi, Oppo and DJI.

Consumer sentiment is also changing. Europeans’ perception of “Made in China” quality and innovation has “improved significantly” over the last 10 to 15 years, said Frank Wang who oversees marketing at Xiaomi -backed Dreame which makes premium home appliances including cheaper alternatives to Dyson hairdryers and vacuums.

The new players are eager to replicate the success of their predecessors. They seek media attention and retail partners at international trade fairs like CES, teach themselves Facebook and Google campaigns, and court gadget lovers on crowdfunding platforms. Investors ranging from GGV Capital to Xiaomi rush to back scrappy startups that are already shipping millions of units around the globe.

For Donny Zhang, a Shenzhen-based electronics parts supplier to hardware companies, businesses have been shrinking as soon as the trade war began. “My clients are taking the brunt because the costs of procurement have increased,” he said of those who directly or indirectly deal with American firms.

While many export-led hardware businesses loathe decreasing profitability, some learn to adapt and look for a silver lining. That has unexpectedly spurred new directions for factory owners in China. Indiegogo, one of the world’s largest crowd-funding platforms, saw the changes first hand.

“Once tariffs increase, there’s not much profit margin left for manufacturers because the middlemen already eat up the bulk of their profit,” Lu Li, general manager for Indiegogo’s global strategy, told TechCrunch.

“A good solution is for factories to skip the middlemen and sell directly to consumers with their own brands. Once the goal of brand building is clear, they often come to us because they need marketing help as a first step to establish themselves as a global consumer brand.”

The trend, dubbed “direct-to-consumers” or D2C, also plays into China’s national plan to encourage manufacturing upgrade and homegrown innovations to compete globally, an initiative that began to take shape around 2015. The development naturally makes China Indiegogo’s fastest-growing region in the last two years: in the first three quarters of 2020, businesses coming from China jumped 50% year-over-year, according to Li.

Localize

Having an appealing product and brand is just the prerequisite. Ever-changing trade policies and geopolitics have forced many Chinese businesses to localize seriously, whether that means setting up a foreign entity or building a local team.

Dreame’s wireless vacuum / Source: Dreame

For Tuya, which provides IoT solutions to device makers around the world, the trade war’s effect has been “minimal” since it has operated a U.S. entity since 2015, which employs its local sales and technical support staff. Most of its research and development, however, still lies in the hands of its engineers in India and China, the latter of which can be a potential contention point, as shown by TikTok’s recent backlash in the U.S.

“The key is compliance. We have a dedicated team of security experts to work on compliance issues. For instance, we were one of the first to get GDPR certified in Europe,” said the company’s chief marketing office Eva Na.

The company’s readiness is prompted by practical needs though. Many of its clients are large Western corporations that demand strict legal compliance in vendors, so Tuya began collecting the needed certificates early on. Connecting 200,000 SKUs today, Tuya’s footprint is found in over 190 overseas countries, which account for over 60% of its business.

Well-funded Tuya may have the financial and operational capacity to sustain an overseas team; but for smaller startups, localization can be a costly and tedious learning curve. Many opted to set up a Hong Kong entity to tap the city’s status as a global financial hub and evade trade restrictions on China, an advantage of the territory that began to crumble following Beijing’s implementation of the national security law.

Balanx, the smart training suit maker, has a Hong Kong entity like many of its export-facing hardware peers. To cope with new global headwinds, it registered a virtual company in Nevada but quickly realized the entity is of little use unless it has an on-the-ground operation in the U.S.

“Many local banks would ask for utility bills and etc. if I want to open an account, which we don’t have. We realized we must have a local team,” asserted the founder.

Hope

Zhang is positive that small companies like his own will remain under the radar in spite of U.S. sanctions. “Just avoid having any government connection,” he said.

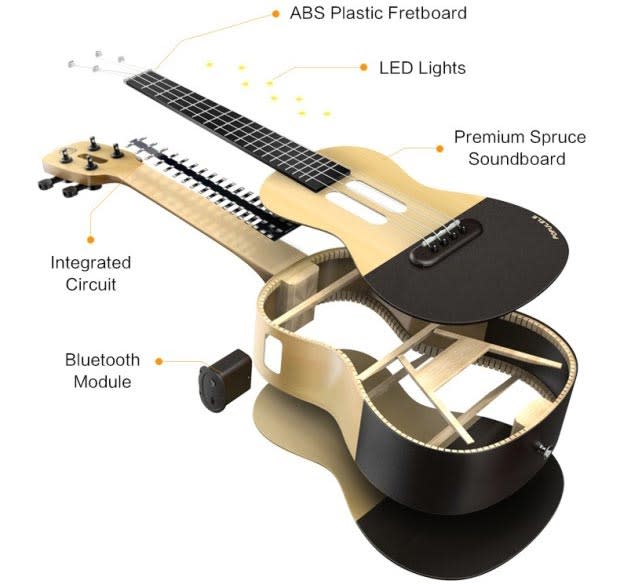

Populele, PopuMusic’s smart ukulele / Source: PopuMusic

Indeed, some of the more “benign” and niche products are continuing to thrive in their global push. PopuMusic, a Xiaomi-backed startup making smart instruments like ukulele and guitar to teach beginners, is one. “We aren’t affected by the trade war. We are in a business that’s neither threatening nor aggressive,” said Zhang Bohan, founder of PopuMusic, which counts the U.S. as one of its biggest overseas markets.

Chinese brands are also seeing their edge as the coronavirus sweeps across the globe and confines millions at home. Hardware makers like Balanx, Dreame and PopuMusic have long learned to master e-commerce and logistics in a country where online shopping is ubiquitous.

“Consumers in Europe and the U.S. are growing more accustomed to e-commerce, a bit like those in China five to eight years ago,” said Wang of Dreame.

Rather than rethinking the U.S., PopuMusic is forging further ahead by launching a new connected guitar via an Indiegogo campaign. Global expansion is at the core of the startup’s vision, the founder said. “We are global from day one. We had an English name before even coming up with a Chinese one.”

In the process of making big bucks, hardware makers may have to downplay their “Made in China” or “Designed in China” brand, said Li of Indiegogo. This could help them avoid unnecessary geopolitical complications and attention in their international push. But one has to wonder how this new generation of entrepreneurs is reckoning with their national pride. How do they deal with the mission passed down by Beijing to promote Chinese innovation in the global marketplace? It’s a line that Chinese entrepreneurs have to tread carefully in their global journey in the years to come.